124th Cavalry

Regiment

124th Cavalry

Regiment

The crest of the regiment is described as: On a wreath of the colors, or and sable, a mullet argent, surrounded by a garland of live oak and olive proper; a shield, divided per bend, or and sable; the Spanish motto, “Golpeo Rapidamente”, which is in English: “I strike quickly.”

The motto is truly a shibboleth, being rigidly observed in all phases of training, which stresses celerity in thought, speech and movement.

The

124th Cavalry Regiment was organized in 1929 and Federally recognized on

March 15 of that year. Previous to its organization, the Texas Cavalry comprised

a regiment of six rifle troops (the 112th Cavalry) and the 56th Machine Gun

Squadron, brigaded with the 111th (New Mexico) Cavalry as the 56th Cavalry

Brigade. It was from the machine gun squadron, plus units of one of the

squadrons of the 112th Cavalry, that the regiment, as now constituted, was

organized.

The

124th Cavalry Regiment was organized in 1929 and Federally recognized on

March 15 of that year. Previous to its organization, the Texas Cavalry comprised

a regiment of six rifle troops (the 112th Cavalry) and the 56th Machine Gun

Squadron, brigaded with the 111th (New Mexico) Cavalry as the 56th Cavalry

Brigade. It was from the machine gun squadron, plus units of one of the

squadrons of the 112th Cavalry, that the regiment, as now constituted, was

organized.

The machine gun squadron furnished to the new unit its Medical Department Detachment, Troop B (San Antonio) became the Regimental Machine Gun Troop, Troop A (Brenham) was redesignated Troop E, and its Major, Calvin B. Garwood, now Colonel of the 124th, was assigned as Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment. Troops E and G, 112th Cavalry, Fort Worth, were redesignated A and B, respectively, and became the First Squadron. Service Troop of the 112th (Mineral Wells) was redesignated Troop F, and its Band Section also joined the new regiment. Headquarters Troop was organized at Austin. The regiment was first commanded by Colonel Louis S. Davidson, former executive officer of the 56th Cavalry Brigade.

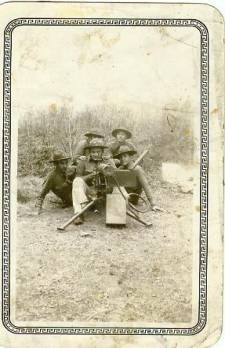

The lineage of the various units of the 124th generally is traced to Texas cavalry deployed during the First World War for Mexican border security service, including the Third, Fifth, and Seventh Texas Cavalry, 1917. Units of the 124th did state duty to enforce martial law at Borger in 1929, in Sherman in 1930, and in the East Texas oil field disorders when the entire 56th Cavalry Brigade (112 Cav /124 Cav) was ordered there in 1931.

On

November 16, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No.

8594, ordering certain units of the National Guard of the United States into

active service of the United States. The order was effective November 18, 1940,

and included the 56th Cavalry BDE. Members were to be inducted for a one-year

period only.

Officers and men were given 10 days to sever civilian ties before moving by

train to Fort Bliss, Texas, near El Paso, their first training station as

members of the Army of the United States. Early in February 1941, the Brigade

received orders to change stations with the 1st Cavalry Division stationed at

the lower border posts. The 56th Cavalry Brigade

Headquarters

and moved to Fort McIntosh at Laredo, Texas. The 112th Regiment relieved the 5th

Cavalry Regiment at Fort Clark, Texas. The 124th relieved the 12th Cavalry

Regiment at Fort Brown in Brownsville and Fort Ringgold at Rio Grande City,

Texas. The troops were becoming acquainted with barracks life when the Brigade

was ordered back to Fort Bliss for desert maneuvers in June 1940, with the 1st

Cavalry Division in Texas and New Mexico. The largest review of Horse Soldiers

since the Civil War took place while at Fort Bliss, made up on the 1st Cavalry

Division and the 56th Cavalry Brigade -- some 13,000 mounted men. Major General

Innis P. Swift stated, "Of all the regiments participating, the 124th was the

most outstanding, both in appearance and performance." Just seven months earlier

they had been weekend civilian soldiers.

Headquarters

and moved to Fort McIntosh at Laredo, Texas. The 112th Regiment relieved the 5th

Cavalry Regiment at Fort Clark, Texas. The 124th relieved the 12th Cavalry

Regiment at Fort Brown in Brownsville and Fort Ringgold at Rio Grande City,

Texas. The troops were becoming acquainted with barracks life when the Brigade

was ordered back to Fort Bliss for desert maneuvers in June 1940, with the 1st

Cavalry Division in Texas and New Mexico. The largest review of Horse Soldiers

since the Civil War took place while at Fort Bliss, made up on the 1st Cavalry

Division and the 56th Cavalry Brigade -- some 13,000 mounted men. Major General

Innis P. Swift stated, "Of all the regiments participating, the 124th was the

most outstanding, both in appearance and performance." Just seven months earlier

they had been weekend civilian soldiers.

The 124th was sent to Fort Brown in Brownsville, Texas where it remained,

patrolling the border. On May 10, 1944, the 124th Regiment moved by train from

the border posts to Fort Riley, Kansas, taking all horses and horse equipment.

At Fort Riley, the Regiment received an A-2 Priority Rating for procurement of

controlled Items of equipment. Personnel adjustments were made, and they

received new men and officers in order to be "combat ready." On July 7, 1944,

the Regiment departed Fort Riley via rail for Camp Anzio, California, a port of

embarkation near Los Angeles, California. Prior to departure, the Regiment

turned in its horses to the Quartermaster at Fort Riley, but loaded all saddles

and other mounted equipment for shipment overseas.

On July 25, 1944, the Regiment boarded the U. S. Ship General H. W. Butner, a

troop transport, bound for India and the ChinaBurma India (CBI) theatre of war.

The voyage ended in Bombay, India on August 26, 1944. From Bombay, the unit

moved by wide gauge rail across the country to the Ramgarh Training Center in

the Province of Bihar, India, some 150 miles West of Calcutta. Here the Regiment

learned that it would be dismounted, but would retain its Cavalry designation.

Orders were received to reorganize into a long-range penetration unit; and the

unit was re-designated the "124th Cavalry (Special)." Mounted equipment was

stored and dismounted type items of clothing were issued.

The Regiment departed Ramgarh, India for Burma on October 20, 1944.

Transportation was on primitive railroad and river steamer up the Brahmaputra

River to Gauhatti, India, then by narrow gauge rail through the Assam Valley to

Ledo; from Ledo to Myitkyina, Burma by C-47 aircraft, then to Camp Landis by

truck. The Regiment arrived in Burma on October 31, 1944. It was here that the

Mars Task Force was formed. This organization contained the 124th Cavalry, the

475th Infantry, a Chinese Combat Team, two Battalions of Field Artillery, some

Quartermaster mule pack troops, and medical and other miscellaneous units needed

in a combat force of such magnitude.

The Mars Task Force was given the mission of clearing Northern Burma of Japanese

forces and opening the Burma Road for truck traffic to China. In order to

accomplish this mission, the force moved more than 200 miles by foot over the

most hazardous terrain in Burma, over mountainous jungles, steep trails, swift

streams and rivers on hot days and cold nights, in rain and mud, coupled with

the ever fear of mite typhus. This was all done while being cut off completely

from friendly forces and having to depend entirely upon air supply. The 124th

established contact with the enemy on January 19, 1945, and fought continuously

for 17 days.

With the objective secure, an administrative bivouac was declared around February 15, 1945.

1st

Lt. Jack Knight, Troop F, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the

only such award for ground action in the China-Burma-India theater. The unit was

demobilized in China on July 1, 1945.

1st

Lt. Jack Knight, Troop F, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the

only such award for ground action in the China-Burma-India theater. The unit was

demobilized in China on July 1, 1945.

POSTWAR SERVICE: On July 2, 1946 several units of the Texas National Guard were organized in the lineage of the 124th. The 124th Mechanized Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron was assigned to the 49th Armored Division and in 1949 became the 2d Squadron of the 124th. Later reorganizations redesignated the 2d Squadron as the 1st and added the 2d Medium Tank Battalion, 124th Armor, elements of the 36th Division

Sgt. Vivian Rodriguez serves Thanksgiving dinner.

![]()

MARS TASK FORCE

A SHORT HISTORY

By Ralph E. Baird

The 5332d Brigade (Prov) was activated on 26 July 1944. It soon came to be known as MARS TASK FORCE. It was designed as a Long Range Penetration Force and training, equipment and organization were all directed toward this end. The following narrative report is submitted. Staff and unit histories, and technical reports are submitted under separate cover.

MARS was able to profit by the experience of Wingate’s Raiders and Merrill’s Marauders in Burma jungle operations. The leaven of veteran jungle fighters was mixed with the freshness of volunteers and the assignment of the 124th Cavalry Regiment. A triangular plan was envisioned and in many ways Mars Task Force was truly a Division, consisting of the 475th Infantry, 124th Cavalry (Sp.) and 1st Chinese Regiment. The Cavalry Regiment had a long history of mounted Cavalry and was converted by Mars to Cavalry dismounted, with the functions and employment of an Infantry Regiment. The 475th Infantry was organized by Mars and given official status as a numbered Infantry Regiment by the War Dept. The Brigade itself was organized as a Provisional Unit.

At no time was Brigade permitted to employ the 1st Chinese Regiment, Sep in any tactical operations. To have been able to use this regiment would have increased the striking power of the Brigade considerably. Although the NAMHPAKKA-HOSI Campaign is considered highly successful, another regiment would have permitted the use of either the 475th Infantry or the 124th Cavalry to swing southward or eastward in a Brigade encroachment of the enemy. It was impossible to do so under the circumstances, for to use one or two Battalion Combat Teams for this purpose would have jeopardized not only such a small striking force but also the holding force. The series of commanding terrain features were such that they had been left open by any Battalion Combat Team it would have been an open invitation to the Japs to surround and destroy the Brigade piecemeal. The 1st Chinese Regiment, later attached to the 50th Division, and committed, demonstrated its ability, and climaxed its campaign by securing KYAUKME and linking with the 36th Division (British). This closed an East-West line. MONG YAI-HSIPAW-KYAUKME-MONGLONG-MOGOK. The British were thus placed in a position to join with the forces of the 14th Army, to establish the line. MONG YAI-HSIPAW-KYAUKME-MAMYO-MANDA-LAY, to terminate the conquest of Northern and North Central Burma.

The Brigade component committed in the TONKWA-MO HLAING sector (475th Infantry) broke Jap opposition in that area and permitted the 50th Division to move in and occupy the area, thence to move Southward to play its part in establishing the line mentioned above.

Upon completion of the action at TONKWA, the Brigade turned to the East and thrust deep into enemy territory to strike the Namhkam-Lashio Burma Road axis, at NAMHPAKKA. The swiftness of movement gained surprise, and the viciousness of attack removed the keystone of the sector. The blow inflicted by Mars at this point caused the enemy to withdraw rapidly below LASHIO and allowed the New First Army (Chinese) to move almost unopposed south of LASHIO, screening against counter-attack and forcing the enemy a safe distance from the STILWELL Road. Brigade was held in the NAMHPAKKA area to be passed through by New First Army. Hence, Mars could not further exploit its own successes. Here contact was broken, and friendly forces belatedly grasped the advantage gained, fulfilling its order in a virtual road march.

The training period of Mars as a Brigade was unusually short. One year is considered the normal training period for a division. Further, all of the Brigade Infantry units, as noticed before, had to be organized (475th Infantry) or converted (124th Cavalry, 1st Chinese Regiment, Sept.)

Throughout tactical operations, the 612th FA Bn (Pk) and the 613th FA Bn (Pk) acquitted themselves with distinction. This was accomplished with the sole aid of 75mm Pack Artillery, constantly opposed by much heavier and longer range enemy weapons (105 and 150mm). The basic intention of Field Artillery - to displace enemy artillery from hostile fire positions against our forces - could not be accomplished by range and striking power. However, in the long run, this was satisfactorily accomplished by attrition and by slow but effective destruction of enemy armament and materiel, as well as by disorganization and damage to motor parks, fuel dumps, warehouses and CP’s (brought within range by the selection of objective). Inability to force earlier displacement of enemy artillery resulted in numerous Brigade casualties.

To reach Brigade objectives, many difficulties previously believed to be well nigh impossible were overcome. That men, mules and fighting equipment can be moved during the monsoons over mountainous Burma jungle trails was indicated. Three days of torrential rain, known as the Christmas monsoons, came during this movement. Trails became running streams of water; narrow paths lacing the edges of the mountain ranges became slippery deathtraps. Necessarily, some mule loads were thrown and animals plunged headlong off trails, but approximately 3000 mules and 7000 men performed the entire movement with the loss of no more than three mule loads. Often mules were hoisted by rope and the load recovered in the same manner. It is a signal tribute the mule leaders who so successfully nursed their hardy charges through these difficulties. Although previous training of the mules had been along herding principles, the Brigade system of a mule leader to each mule paid rich dividends. Perimeter defense was securely established each night and wide reconnaissance patrols kept active.

In the movement from NANSIN to NAMHPAKKA, topography was unfavorable. Forbidding ranges were traversed. Above the SCHWELI RIVER these were sometimes so exhausting as to permit only one or two minutes of moving, followed by five minutes of rest. Terrain permitted, for example, one day’s move of only 3-1/2 miles. A reasonable time table was nonetheless maintained. Despite hardships, upon arrival of the objective the Brigade attacked without delay with high combat efficiency.

Although the popular picture of BURMA warfare is portrayed by steaming jungles, elevations as great as 8000 feet were surmounted. On three successive days of fair weather, water froze in canteens and helmets. These extremes in climate did not result in illness to the troops, even though but one blanket and poncho per man constituted the entire bedding. Fires were out of the question for wandering groups of Japs were always a threat.

Mules survived almost 100% and arrived in excellent condition. As distance traveled increased, the ratio of soldier march fractures went up. Men who otherwise would have remained effective under shorter overall distance, found their metatarsal arches breaking down and a high percentage of such casualties had to be evacuated.

At times evacuation difficulties were a cause of deep concern to the entire command. Air Liaison could not function. No motor roads were available. Natives had vanished, were unemployable, or were felt untrustworthy for this work. Animals were prime loaded with loads and also unsuitable for evacuation. The line of communications was vulnerable to ambush, and blockade by the enemy. It was necessary to withhold a Rifle Company to escort and carry through evacuees for a period of four days. Evacuation at this time was to MONGWI where a Liaison plane strip served evacuation to the rear. Hemmed in as this strip was by rough mountains, the burden of evacuation was heavy. On several occasions, evacuation parties were able to come within one mile of this strip and unable to reach it before nightfall. It is considered a benevolent stroke of good fortune that evacuees were brought in without exception.

When ordered out for a conference, the CG, 532nd Brigade (Prov) covered in a forced mule back ride of one day, the distance traveled by the foot elements in three days marching. Traveling mounted with a single companion reduced the number of obstacles that confronted mass movement.

Although one blanket and poncho provided the only protection against bitterly cold nights, substantial weight was thereby added to the individual pack. No instances of pack paralysis occurred. However, the weight is considered a contributing factor to march fractures. To accomplish Long Range Penetration, it was necessary for each man to carry essential items. These were stripped to the minimal by such measures as having each individual carry a spoon, and the top of the meat can, in some instances only a spoon and canteen cup. Two canteens were necessary for all water had to be boiled or treated before consumption. Rations, jungle kit, machete, jungle knife, individual weapons and ammunition had to be man carried as well as shoes, clothing and toilet articles. Compasses were carried by all. Mule loads, such as guns and signal equipment sometimes amounted to 350 pounds. Green fatigues and combat boots, or GI shoes with leggings proved satisfactory as a jungle uniform. Jungle boots were generally used for relief. Helmets were worn except in certain night patrolling.

Throughout the movements, air drop was the only source of rations and other resupply. No more than three days rations could be carried. The country seldom offered fair air drop sites, and frequently a high percentage of the drops was impossible to recover in precipitous wooded areas.

To accomplish the Brigade mission of cutting the Burma Road at NAMHPAKKA, it was necessary to seize extensive battalion objectives. The controlling features were independent broad hills and high ranges. To leave one unoccupied was to leave the enemy in a commanding position. LOI KANG Ridge, for example, extended approximately two miles in length. rising between the long valley on the west and open stretch of the Burma Road on the east. No cover or defiles existed on this sector of the Burma Road. The Japs were well entrenched on LOI KANG Ridge and held two villages (LOI KANG and MAN SAK) which nestled high in its wooded recesses. Only surprise and a quickly prosecuted attack by the second battalion upon its reaches could have ousted the enemy. The attack had to be made up sheer walls and base tactics of fire and movement wrenched this ground from enemy hands. Gaining the northern crest it was necessary for this battalion to turn south and fight down the axis of the range, yard by yard drawing the enemy back until another battalion (1st Bn. 475th Inf.) had seized its objectives and organized the ground. This battalion then executed a limited encirclement of the LOI KANG enemy forces. Thereafter, the 2nd Battalion was secure upon the ridge, enemy forces having been killed or forced to decamp. A trail along the only passage this range had 80 individual pillboxes in a 100-yard area that had to be cleaned out. Continuous enemy counter-attacks was pressed. The 1st Battalion had to be withdrawn immediately after its participation in this attack to protect the hill features it had secured to the west of LOI KANG Ridge.

During this operation each Bn combat Team had its hands full with its respective objective, all being high ground features commanding the road. Continuously, however, ambushes, combat patrols, roadblocks, automatic weapons, fires, mines and artillery were used on the road by all battalions and squadrons. Even before the heights were fully taken, the enemy situation had become such that in his withdrawal from the north he had to cease all day movement over the road; soon all night movement. The equipment and troops he was able to extricate from the north had to go over the network of roads previously constructed well east of the Burma Road and out of range of MARS fire power. Many of his wounded, and perhaps many of his dead, were taken southward toward LASHIO through the corridors east of the Burma Road.

Disregarding enemy numbers not confirmed as killed, a ratio of six and one half Japs to one American was established.

During these operations, the only equipment to fall into enemy hands was one small radio set. It is possible, but not confirmed, that one American prisoner was taken. One 75mm piece suffered a direct hit and three others were damaged, but replacement parts put these guns in action on the succeeding day.

Both air drop supply of all classes and Liaison plane evacuation of the wounded were under enemy fire throughout this campaign. Air currents were treacherous and inadequate Liaison strips were all that could be devised.

Little malaria existed, except recurrences of earlier contraction. Precautions against typhus and dysentery; as well as malaria, were constantly impressed, but some inevitably was suffered. Only one latent neurosis developed.

Mules were controllable in proximity to hostile and friendly fire. Bamboo cutting made nutritious provender when the tactical situation prevented loose grazing.

During the campaign MARS introduced to combat use, the night sighting devices known as Snooperscopes and Sniperscopes. These were received in the midst of operations and hasty acquaintance with the instruments was all that could be had. Tactics were established for the use of these on the ground.

At the conclusion of this campaign, MARS was a well-knit and experienced force, all elements having undergone combat, new techniques devised, lessons learned, morale high, leadership seasoned.

![]()

Strategic Overview 1944

By

late October 1944 it was clear that final Allied victory in Burma was only a

matter

of time. In June and July the British had decisively defeated the invading

Japanese Fifteenth Army at Imphal, removing the threat to India and opening

the way for a British counteroffensive into Burma. After Imphal the British IV

and XXXIII Corps pushed to the Chindwin River, while the XV Corps prepared to

advance down the Burmese coast: General Sultan could now call on one British and

five Chinese divisions, as well as a new long-range penetration group known as

the "Mars Task Force." This brigade-size unit consisted of the 475th Infantry,

containing the survivors of GALAHAD, and the recently dismounted 124th Cavalry

of the Texas National Guard. The Allies possessed nearly complete command of the

air. CBI's logistics apparatus was well established, and the leading bulldozer

on the Ledo Road had pushed to within eighty miles of the road from Myitkyina

south to Bhamo. From that point the engineers needed only to improve existing

routes to the old Burma Road, fifty miles south of Bhamo. Myitkyina had grown

into a massive supply center with an expanded airfield and a pipeline. Sensing

victory, the Allies planned to continue their advance in two phases, first to

Bhamo and Katha, then to the Burma Road and Lashio.

matter

of time. In June and July the British had decisively defeated the invading

Japanese Fifteenth Army at Imphal, removing the threat to India and opening

the way for a British counteroffensive into Burma. After Imphal the British IV

and XXXIII Corps pushed to the Chindwin River, while the XV Corps prepared to

advance down the Burmese coast: General Sultan could now call on one British and

five Chinese divisions, as well as a new long-range penetration group known as

the "Mars Task Force." This brigade-size unit consisted of the 475th Infantry,

containing the survivors of GALAHAD, and the recently dismounted 124th Cavalry

of the Texas National Guard. The Allies possessed nearly complete command of the

air. CBI's logistics apparatus was well established, and the leading bulldozer

on the Ledo Road had pushed to within eighty miles of the road from Myitkyina

south to Bhamo. From that point the engineers needed only to improve existing

routes to the old Burma Road, fifty miles south of Bhamo. Myitkyina had grown

into a massive supply center with an expanded airfield and a pipeline. Sensing

victory, the Allies planned to continue their advance in two phases, first to

Bhamo and Katha, then to the Burma Road and Lashio.

|

Aerial view of the first convoy to go from India to China over the re- opened Burma Road. (DA photograph) |

The offensive resumed on 15 October. While the main British force to the southwest completed its push to the Chindwin, Sultan advanced three divisions toward the Katha-Bhamo line. To the west the British 36th Division, after overcoming stubborn Japanese resistance at the railway center of Pinwe, encountered no opposition until its occupation of Katha on 10 December. In the center the Chinese 22d Division likewise encountered little initial opposition, occupying its objective of Shwegu without incident on 7 November. South of Shwegu the 22d ran into advance elements of the 18th Division near Tonkwa on 8 December. Since the 22d Division was scheduled to leave the front for China, the 475th Infantry replaced the Chinese and held its ground against repeated assaults until the Japanese withdrew. Meanwhile, the Chinese 38th Division on the left flank had skillfully used flanking movements to drive the Japanese on its front into Bhamo. After a delaying action the Japanese evacuated Bhamo on 15 December and withdrew south toward Lashio. |

Reaching the Burma Road now lay within the grasp of the Allied forces. The next phase of the campaign would involve a larger role for the Mars Task Force. General Sultan wanted to send the force up the line of the Shweli River to threaten the Burma Road and the rear of Japanese forces opposing the advance of the Chinese 38th and 30th Divisions from Bhamo. But the 124th Cavalry, many of whose troopers still wore the old high-top cavalry boots, first had to make the killing hike from Myitkyina south through the rugged mountains to the Shweli. Making their way along narrow paths which took them from deep valleys to peaks above the clouds, the men of the 124th finally reunited with the 475th at the small village of Mong Wi in early January 1945. From there the Mars Task Force moved east to drive the enemy from the hills overlooking the Burma Road. Bringing up artillery and mortars, the Americans opened fire on the highway and sent patrols to lay mines and ambush convoys. After the experience with GALAHAD, however, Sultan and the force's commander, Brig. Gen. John P. Willey, were anxious not to risk the unit's destruction by leaving it in an exposed position astride the road.

The Mars Task Force may not have actually cut the Burma Road, but its threat to the Japanese line of retreat did hasten the enemy's withdrawal and the reopening of the road to China. While Y Force advanced southwest from the Chinese end of the Burma Road toward Wanting, the Chinese 30th and 38th Divisions moved southeast toward Namhkam, where they were to turn northeast and move toward a linkup with the road at Mong Yu. To oppose this drive, the Japanese had deployed the 56th Division at Wanting, troops of the 49th Division at Mong Yu, and a detachment at Namhkam, but these units planned to fight only a delaying action before retreating south to join the defense of Mandalay. They withdrew as soon as the Chinese applied pressure. As the Marsmen were establishing their position to the south, the 30th and 38th Divisions captured Namhkam and drove toward Mong Yu. On 20 January advance patrols of the 38th linked up with those of Y Force outside Mong Yu. Another week proved necessary to clear the trace of any threat from Japanese patrols and artillery fire, but on 28 January the first convoy from Ledo passed through on its way to Kunming, China. In honor of the man who had single-mindedly pursued this goal for so long, the Allies named the route the Stilwell Road.

Analysis

Historians have found it fashionable to characterize the CBI as a forgotten theater, low in the Allied list of priorities. To be sure, the European, Mediterranean, and Pacific theaters all enjoyed greater access to scarce manpower and material than the CBI, which had to cope with an extended line of supply back to the United States. Only a few American combat troops served in China, Burma, or India. Yet one can hardly call the CBI an ignored theater. It occupied a prominent place in Allied councils, as Americans sought an early Allied commitment to reopening China's lifeline so that China could tie down massive numbers of Japanese troops and serve as a base for air, naval, and eventually amphibious operations against the Japanese home islands. The American media, with its romantic fascination with China and the Burma Road, followed the campaigns closely and kept its audience informed on Vinegar Joe Stilwell and Merrill's Marauders. Interest in the theater did drop after early 1944 as estimates of China's military capability declined, but Allied leaders continued to keep a close eye on developments in a region where they still felt they had much at stake.

For the American supply services, their performance in the CBI theater represented one of their finest hours. The tremendous distances, the difficult terrain, the inefficiencies in transport, and the complications of Indian politics presented formidable obstacles to efficient logistics. Nevertheless, by early 1944, American logisticians had developed an efficient supply system whose biggest problem was the time needed to ship material from the United States. The supply services expanded the port capacity of Karachi and Calcutta, enhanced the performance of India's antiquated railroad system through improved maintenance and scheduling, and developed techniques of air supply to support Chinese and American forces in the rugged terrain of North Burma. Despite the skepticism of the British and other observers, American engineers overcame the rugged mountains and rain forests of North Burma to complete the Stilwell Road which, joined to the old Burma Road, reopened the line to China. A tremendous feat of engineering, the Stilwell Road deservedly earned considerable applause.

Stilwell himself has received more mixed reviews. A fine tactician, he maneuvered his Chinese-American forces with considerable skill in the campaign to drive the Japanese from the Hukawng Valley, and he showed commendable boldness in the decision to strike for Myitkyina before the monsoon. In the end the gamble barely paid off, but it did succeed. Stilwell's record indicates that he would have likely performed quite well as a division commander in Europe, the role that Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had in mind for him before his appointment to the CBI theater. Unfortunately, most of Stilwell's responsibilities at the CBI emphasized administration and diplomacy, areas for which he possessed much less aptitude than for field command. He had little patience for paperwork, and he lacked the tact to reconcile the differing viewpoints of the nations involved in the CBI. Admittedly, in his three years in the theater, he probably held more concurrent positions than should ever have devolved on one man.